Introduction to mathematical induction for programmers part 2 - Trees, Grids, and infinite chains

In a previous post, I wrote up an overview of the concept of induction as a mathematical proof tool and related it to programming problems and recursive algorithms. My main point is that induction is not just a way to prove cute mathematical identities, but a way we can reason about solving problems algorithmically. If you didn’t read that post, I really recommend reading that first as I build directly on top of it here.

In that post, I did some quick examples on problems on arrays, and showed that even on just arrays, the dependency structures of the recursion are not always just simple linear chains. At the end of the post, I hinted that dependency structures come up quite often in programming, not just in problems that deal with arrays. In fact, with problems using other data structures, the dependency structure can be even easier to reason about, such as in problems with trees. I’ll be doing examples with other data structures here to highlight that.

Also, I want to highlight the importance of the dependency structure having finite dependency chains. In the problems I did in the last post, I ended up just directly coming up with dependency structures that had finite dependency chains already. However, infinite dependency chains can come up if we’re not careful, often resulting in practice as an infinite loop or recursion. So I’ll show an example where an infinite dependency chain causes problems.

So let’s just head into those examples. I wrote the first blog post partially for my roommate Kevin, and he wanted some of these follow-ups that I mentioned in this post. He also wanted me to somehow incorporate his romantic preferences as a theme for an example. I’m not quite clever enough to do that, so if you want, just imagine that the numbers are actually female asian coworker graphic designers 1.

Induction on tree structures

Let’s start with a problem on trees, one that is hopefully easy to understand as a statement so that we can just focus on dependency structures.

Problem: Consider a binary tree of numbers t, make a function tree_depth(t) that returns

the depth of the tree. The depth of a tree is the maximum length of a path from the root to

any of the leaves.

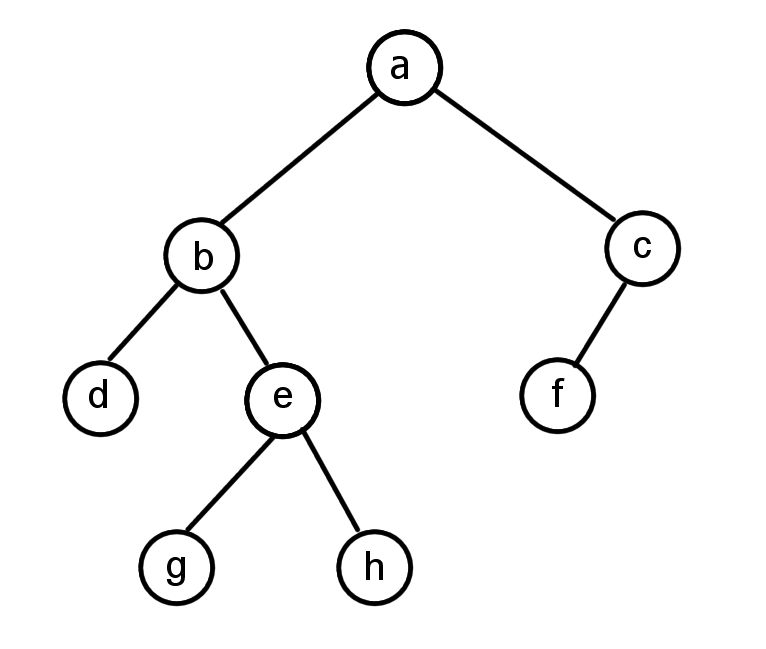

Example: Consider the tree below. The path a - b - e - g or a - b - e - h are paths from the root a to a leaf of length 4. All other paths have length less than 4. So the depth of this tree is 4.

As in the previous post, we’ll try to reason about how the solution for a bigger problem can be derived from the solutions of other problems. Our bigger problem is then said to have those other problems as “dependencies”. Here, the tree structure already gives the dependency structure we need. For example, if we somehow knew the depth of the subtrees rooted at node b and node c, then we would also know the solution for the full tree rooted at a. It would be the maximum of the 2 depths of the trees from either node b or node c, plus 1 for node a itself. In the example, the depth of the subtree rooted at node b is 3 (b-e-g or b-e-h) and the depth of the subtree rooted at node c is 2 (c-f). So the depth of the tree rooted at node a is 4, which represents the paths a-b-e-g or a-b-e-h.

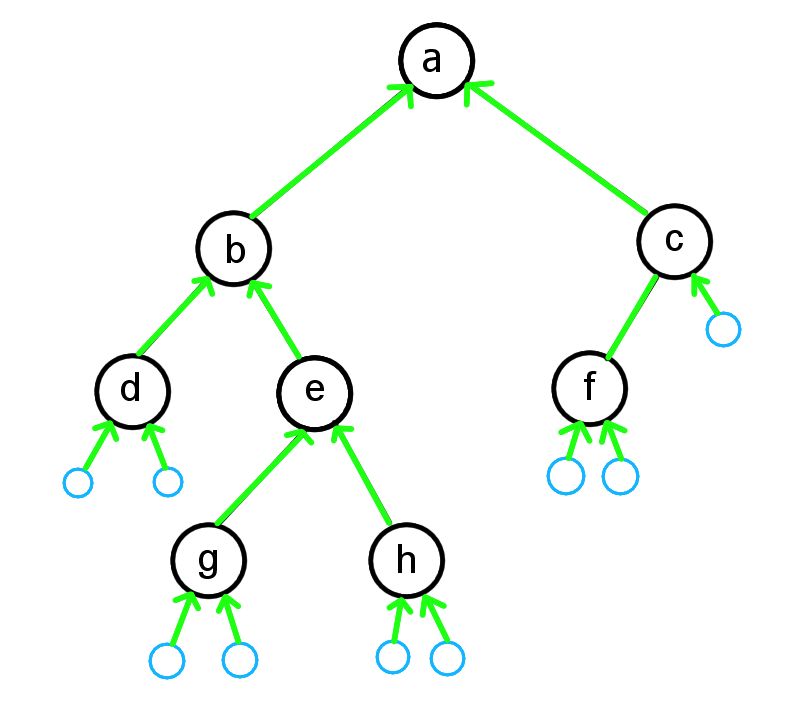

So the tree itself mostly already reflects a useful dependency structure. But we also need a case to end our dependency chain, some case that is easy to reason about without other dependencies. Otherwise, we’ll never get our chain of deductions started. A node with no children (i.e. a leaf, such as node g in the example) is a good example, as it’s clear a tree rooted at such a node has depth 1. But then we would have to also handle cases where the node may only have only one of either its left or right child. It’s slightly more convenient to instead use the null node (which represents the empty tree) as the starting case, which has depth 0. We can think of a null left or right child pointer as pointing to this empty tree.

Here is the revised dependency structure for our example tree. The blue nodes are the empty tree nodes that were added to make the solution a little easier.

In this example, to solve the tree for node a, we would depend on the solution for node b and c, which themselves have their own dependencies to resolve. Eventually the dependency must end at one of the empty nodes, which we can immediately declare has a depth of 0. Then we can work our way back up the dependency chains and eventually get to the solution for node a (which we know to have a depth of 4).

Even though this dependency structure is specific for our example tree, the process to construct the dependency structure for any (finite) binary tree is very similar. We just use the edges of the tree and logically add some extra empty nodes whenever a node doesn’t have all its children set.

Like in the examples in the previous post with arrays, the dependency structure naturally gives a recursive algorithm to solve it.

The code ends up really simple, but that’s the point! In many cases, just coming up with a natural dependency structure will result in easy to express code.

Induction on grids with infinite dependency chains

But how can we do the dependencies in the wrong way? A common problem to look out for is a situation with possibly infinite recursion, which happens quite a bit in search problems on general graphs.

Let’s consider this example problem on a 2D grid:

Problem: Consider a N by M grid of positive numbers g (expressed as an array of arrays). Make a function min_grid_path(g) that returns

the minimum path from the top-left corner (0, 0) to the bottom-right corner (N-1, M-1).

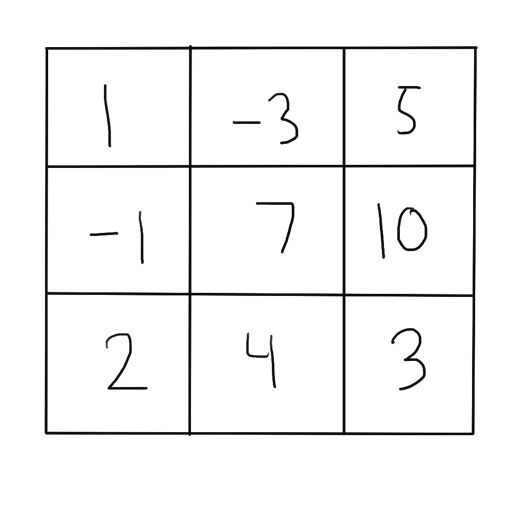

Example: Consider the 3 by 3 grid below. The min path goes from (0, 0) down to (1, 0) and (2, 0), and then goes right to (2,1) and (2,2). The min path value is 1 + 5 + 2 + 4 + 3 = 15.

The reasoning about the min path in this grid is very similar to the skip path example in previous post. The min path that comes to the bottom-right corner must have arrived there via the grid locations next to it, so via either (N-2, M-1) or (N-1, M-2). The subpath up to that penultimate location must also be the minimum such path to get there. So we can say that the min path to get to (N-1, M-1) is dependent on the min paths to both (N-2, M-1) and (N-1, M-2). Once we get to the middle of the grid, some grid elements will be dependent on its 4 cardinal neighbors. In our 3 by 3 example, the min path to (1, 1) is dependent on the min paths to (0, 1), (1, 0), (1, 2), and (2, 1).

To apply induction, we need a case that we can easily reason about without dependencies. That case is the path that ends at the starting point (0, 0). The minimum path post from (0, 0) to (0, 0) is clearly just the value of the grid at (0, 0) itself. Since we have a dependency structure of solutions depending on other solutions, and a case to stop the dependency chains, it may seem we can just do the same application to get to a recursive algorithm.

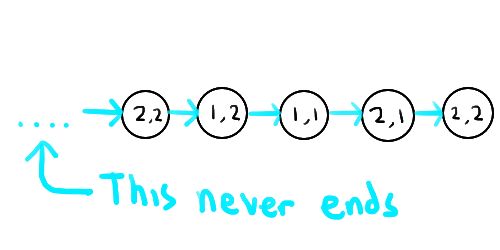

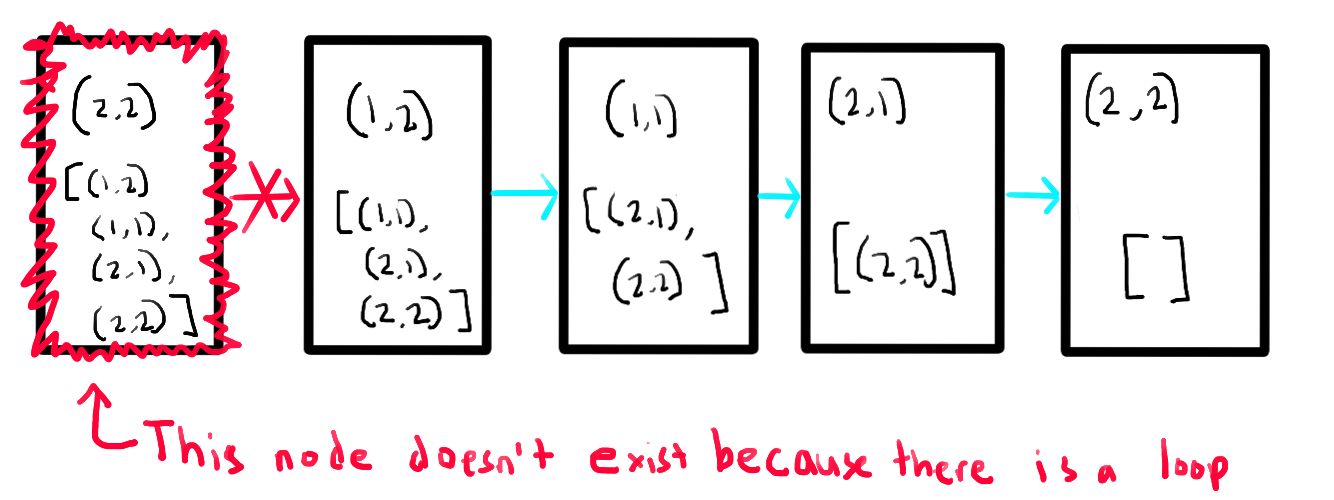

However, there’s a problem here. The dependency chains here aren’t finite. We have to protect ourselves from an infinite loop that doesn’t ever get to (0, 0), such the 4 location loop from (2, 2), (2, 1), (1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 2), and so on. This creates a dependency chain that doesn’t end at an easy case, so we have no place to start applying induction from.

Aaaaaah, it never ends!! In magical theoretical computers at least. Real computers would just throw a stack overflow exception at you.

If you’re familiar with algorithms, you probably might already know how to fix this problem. Since all the costs are positive, we can cut off any loops in a path and end up with a path with smaller cost that has the same starting and ending point. That is, any minimal path must have no loops in it. So we can just ignore any option that would go through a node we’ve already seen and thus introduce a loop.

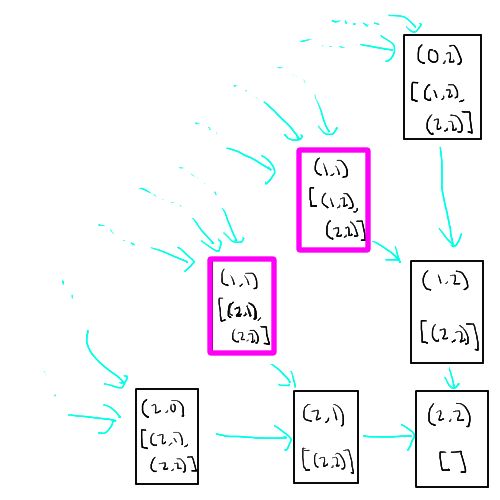

The way we would implement that idea in code is by keeping a set of nodes we’ve already seen in our search. We can fix this infinite dependency chain issue using the same idea. The nodes in our dependency chain can represent the combination of a target ending location and a set of the nodes that will be taken afterward to get to (2, 2). So for example, the combination of (end location - (1, 1), path - [(2, 1), (2, 2)]) would be distinct from the combination of (end location - (1, 1), path - [(1, 2), (2, 2)]). We would reconstruct the dependency chain such that a combination would only depend on combinations that have end locations neighboring its own end location (like before), but the neighboring location can’t already be in the path that would follow (because that would introduce a loop).

This is hopefully more clear if we try to redraw the infinite dependency chain as before and show how it breaks the infinite chain:

The infinite dependency chain is fixed because the problematic node that would cause the loop doesn’t actually exist! Sometimes the way to fix a problem is just to make sure it doesn’t exist on the first place.

The overall dependency structure does branch out though, and note that we now have different nodes for subproblems that may end at the same location, but the ending paths are different.

A sample of the dependency structure all ending at the target location (2, 2) with an empty path afterward. Note that the boxes highlighted in pink represents a subproblem that end at the same location (1, 1), but they’re different due to a different path afterward.

If we restructure the dependency structure this way, we can actually show that each dependency chain must be finite. Each step back the dependency chain must introduce a new node to the accumulated path, and there’s only a finite amount of new nodes to add before we run out. So these chains must eventually end. But they don’t necessarily end at the starting location we want, (0, 0). These chains might end in a way that we can’t get back to the starting location. For example, the subproblem of a path that would end at (1, 2) with a path afterward of [(0, 2), (0, 1), (1, 1), (2, 1), (2, 2)] is impossible since all of the neighbors of (1, 2) are in the set of nodes that cannot be visited again. However, because they’re impossible, these solution for these cases are also really easy to calculate without other dependencies, so we can treat these as base cases too! We’ll just mark these paths as having cost infinity to represent impossibility.

To summarize, the new dependency structure has nodes that represent a subproblem that is a combination of a target ending location (from the known starting location (0, 0)) and path that will be taken afterward. The original problem is the subproblem that targets ending at (2, 2) with an empty path afterward. As above, we can make a dependency structure such that each chain is finite. A chain either ends at:

- a subproblem that targets ending at (0, 0) with any path afterward, which we can immediately assign the cost of just the cost at (0, 0).

- a subproblem that targets ending at a location that has all neighbors being in the path afterward already, so we’ll assign the cost of infinity to represent an impossible problem.

Since each chain is finite, we can apply induction and say we’ve solved the original problem! 2 We can then take this dependency structure to come up with a recursive implementation:

The code here is much longer than the previous code example, but much of this is just repeated code for the four cardinal directions which could become more compact with some restructuring. Conceptually, the translation to code is the same - handle cases that we can do without dependencies directly, otherwise recursively solve subproblems according to the dependency structure we constructed.

Wrapping up

In this post, I just wanted to follow up on a previous post with some examples not using arrays, and also wanted to highlight the importance of finite dependency chains and how to break up an infinite dependency chain, e.g. by making such a chain invalid. Just like the previous post, the dependency structures can directly be translated into recursive algorithms.

If you enjoyed this post, have any questions, comments, suggestions about what to think about next, or just want to say hi, just email me at me@lalaheadpats.com.

Footnotes

-

The female asian coworker graphic designers should be single and available of course. For example, I could prove that he’ll date all such people by induction:

- He will date the first such person

- If he dates one such person, he will date the next such person

This isn’t exactly a mathematical proof because the concept of “will date” isn’t a rigorous mathematical statement. But empirical evidence has shown that these rules have good support, so I think it’s a good conjecture that will be proved in the next century. ↩

-

We haven’t exactly showed that we solved the original problem yet. All this shows is that the algorithm ends at some point, not that we necessarily find the minimal path. We still need to at least show that the minimal path shows up somewhere_in this dependency chain. That’s actually not that hard to reason about - our dependency structure is going through all paths without loops backwards and since the minimal path doesn’t have any loops, one of the dependency chains will represent the minimal path. I just didn’t want to distract from the main point restructuring the dependencies to make induction work. ↩